I created a project gzip.go, which is a toy implementation to decrompress zip file. The blog content below is copied from the README. It aims to explain the techniques used in Gzip.

gzip.go

The implementation is largely derived from http://www.infinitepartitions.com/art001.html, but I try to add some overview explanations.

Technique 1: Huffman Encoding

What is encoding? Encoding is mapping from symbols to another symbols. In this case we will map the symbol to binary values, which we will simply call as codes. It is important that the encoded result must be decode-able. Some (invalid) mapping can cause the encoded data to be undecode-able because of ambiguity.

Basic example

One example of encoding, is let say, encode the 4 shapes of a card set, as such:

| Shape | Code |

|---|---|

club |

00 |

heart |

01 |

spade |

10 |

diamond |

11 |

club, heart, spade, and diamond into some binary values, for example, 00, 01, 10, 11. In this way, a string of codes like 01101111 can be decoded as heart, spade, diamond, diamond.

In this particular encoding, we are using 2 bits for each symbol, hence the average length of the codes are 2 bits as well.

Encoding Performance

In most cases, the main goal of an encoding system is to reduce space. That is equivalent to minimizing the average length. An example of a very redundant encoding system is to encode the symbols as ASCII characters, simply like mapping:

| Shape | Code |

|---|---|

club |

club |

heart |

heart |

spade |

spade |

diamond |

diamond |

In this case, the average length is (4 + 5 + 5 + 7)bytes/4 = 5.25 bytes = 42 bits. This is 21 times longer than our previous 2-bits encoding.

Can we do better than 2-bits? How about this following encoding?

Invalid encoding and lower-bound of information

| Shape | Code |

|---|---|

club |

0 |

heart |

1 |

spade |

00 |

diamond |

01 |

Assuming that all shape has equal frequency of appearance, this encoding has an average length of 1.5 bits.

However, there is an issue with this encoding. When we encounter the code 00, we don’t know if it should mean 2 clubs or 1 spade. So we call this invalid encoding.

So seems like the 2 bits encoding is the best one for now. But how do we know or how do we prove it? We can have another valid encoding that is not of equal length, or which we can call “variable length encoding”, for example:

| Shape | Code |

|---|---|

club |

1 |

heart |

01 |

spade |

001 |

diamond |

0001 |

This doesn’t have ambiguity in the decoding state, but the average bit length is 2.5.

But all this while we only talk in the assumption of the frequency being equal. Assume we have a different card sets that has different frequency of shapes:

| Shape | Frequency |

|---|---|

club |

0.5 |

heart |

0.3 |

spade |

0.1 |

diamond |

0.1 |

In this case, to measure the encoding performance, we cannot simply take the average bit length, but rather we need to weight it against the frequency.

| Shape | Frequency | Fixed Length Enc | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

club |

0.5 | 00 |

1 bit |

heart |

0.3 | 01 |

0.6 bit |

spade |

0.1 | 10 |

0.2 bit |

diamond |

0.1 | 11 |

0.2 bit |

*Because we are talking in terms of expectation / frequency, we can use non-integer value for “bit count” despite bit being a discrete measure.

Here, the fixed-length 2-bit encoding uses about (1 + 0.6 + 0.2 + 0.2) = 2 bits per symbol (following the symbol frequency/distribution). This is not very surprising because regardless of the frequency distribution, each symbol contributes the same amount.

Let’s compare it with our variable length encoding:

| Shape | Frequency | Variable Length Enc | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

club |

0.5 | 1 |

0.5 bit |

heart |

0.3 | 01 |

0.6 bit |

spade |

0.1 | 001 |

0.3 bit |

diamond |

0.1 | 0001 |

0.4 bit |

Here, the sum of contribution is 1.8 bits.

In fact, we can make the encoding shorter:

| Shape | Frequency | Variable Length Enc | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

club |

0.5 | 1 |

0.5 bit |

heart |

0.3 | 01 |

0.6 bit |

spade |

0.1 | 001 |

0.3 bit |

diamond |

0.1 | 000 |

0.3 bit |

This encoding might be slightly less intuitive, but consider streams like 000010010001 can be decoded easily as:

000010010001

This encoding has the total contribution of 1.7 bits per symbol. It can be proven that this encoding is the most optimal one for such frequency distribution.

Huffman Algorithm

Huffman Algorithm is an algorithm to generate huffman encoding. Huffman Algorithm works on the distribution of the symbols and will generate an optimal* encoding for the set of symbols.

*this method is only optimal for if we want to encode one symbol at a time (can be proven). If we remove that constraint and we can encode strings of symbols instead, we can do better compression (lower average bits per symbol).

Algorithm:

0. Given n symbols with probability/frequency of p_0, p_1, …, p_n

- Build subtree using 2 symbols with the lowest

p_i. - At each step, choose 2 symbols/subtrees with the lowest total probability/frequency, combine to form new subtree

- Result: optimal tree built with bottom-up

- Apply

0to left edge and1to right edge (or vice versa, doesn’t matter)

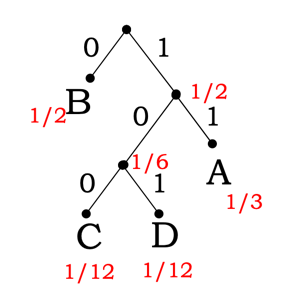

Example:

| Shape | Frequency |

|---|---|

A |

1/3 |

B |

1/2 |

C |

1/12 |

D |

1/12 |

Thus, we will get encoding of:

| Shape | Encoding |

|---|---|

A |

11 |

B |

0 |

C |

100 |

D |

101 |

Read more: https://computationstructures.org/lectures/info/info.html (Entropy, Huffman Algorithm)

Huffman Trees Encoding

So far we have only discussed huffman trees in the abstract or in your program’s memory. How do we actually encode this? The naivest solution will simply be listing out the symbol and encoding one after another:

| Symbol | Encoding |

|---|---|

A |

11 |

B |

0 |

C |

100 |

D |

101 |

But this is not very efficient. One improvement that we can do is to skip listing out the symbol instead because we can pre-agree on what are the symbols are.

| Encoding |

|---|

11 |

0 |

100 |

101 |

Next thing that we can improve, is actually we don’t have to provide all the encoding, simply giving the bitlength is enough to build a reproducible tree. This is possible because what really matters in huffman tree is the length for each symbol encoding, not the structure of the tree itself.

| Encoding |

|---|

| 2 |

| 1 |

| 3 |

| 3 |

Here’s one way to fill it

0000: 0

0001: 1

101100: 2 <- start a new sequence at (10101 + 1) << 1

101101: 3

101110: 4

0010: 5 <- pick up four-bit sequence where it left off

0011: 6

01110: 7 <- start a new sequence at (0110 + 1) << 1

01111: 8

10000: 9

10001: 10

10010: 11

10011: 12

10100: 13

10101: 14

101111: 15 <- pick up six-bit sequence where it left off

110000: 16

110001: 17

110010: 18

0100: 19 <- pick up four-bit sequence where it left off

0101: 20

0110: 21

110011: 22 <- pick up six-bit sequence where it left off

110100: 23

110101: 24

110110: 25

110111: 26

The next step is to, instead of providing all the bit lengths, we can provide it as RLE instead:

func TestRLE(t *testing.T) {

values := []int{

3, 0, 0, 0, 4, // 0-4

4, 3, 2, 3, 3, // 5-9

4, 5, 0, 0, 0, // 10-14

0, 6, 7, 7, // 15-18

}

expectedRanges := []rleRange{

{0, 3},

{3, 0},

{5, 4},

{6, 3},

{7, 2},

{9, 3},

{10, 4},

{11, 5},

{15, 0},

{16, 6},

{18, 7},

}

assert.Equal(t, expectedRanges, runLengthEncoding(values))

}

If you are worried about RLE having more overhead than the benefit, note that we have about 285 codes in total in GZIP, which probably will have bit lengths of up to 10. We should have more consecutive values, especially where there’s a lot of 0s.

The actual RLE system used in GZIP:

for i < alphabetCount {

code, _ := getCode(stream, codeLengthsRoot)

// 0-15: literal (4 bits)

// 16: repeat the previous character n+3 times (2 extra bits specified)

// 17: insert n 0's (3 bit specified), max value is 10

// 18: insert n 0's (7 bit specifier), add 11 (because it's the max of code 17)

if code == 16 {

repeatLength := readBitsInv(stream, 2) + 3

for j := 0; j < repeatLength; j++ {

alphabetBitLengths[i] = alphabetBitLengths[i-1]

i++

}

} else if code == 17 || code == 18 {

var repeatLength int

if code == 17 {

repeatLength = readBitsInv(stream, 3) + 3

} else {

repeatLength = readBitsInv(stream, 7) + 11

}

for j := 0; j < repeatLength; j++ {

alphabetBitLengths[i] = 0

i++

}

} else {

alphabetBitLengths[i] = code

i++

}

}

The instructions above actually contains very clever designs:

- for code 16, always add 3 times. Because if it only repeated 2 times, it’s the same as directly write the codes (using 2 symbols). Using code 16 means we need to specify code

16, then0b11. - same technique applied for code 17

- for code 18, since for repetition count 4-10 is already covered, we can directly jump to

11.

Finally, these codes from 0-18 are huffman-encoded as bit-lengths:

func readCodesBitLengths(stream *bitstream, hclen int) []int {

// The specification refers to the repetition codes as the values 16, 17, and 18,

// but these numbers don't have any real physical meaning

// 16 means "repeat the previous character n times",

// and 17 & 18 mean "insert n 0's".

// The number n follows the repeat codes and is encoded

// (without compression) in 2, 3 or 7 bits, respectively

// Because codes of lengths 15, 1, 14 and 2 are likely to be very rare in real-world data,

// the codes themselves are given in order of expected frequency

codeLengthOffsets := []int{

16, 17, 18, 0, 8, 7, 9, 6, 10, 5, 11, 4, 12, 3, 13, 2, 14, 1, 15,

}

codeBitLengths := make([]int, 19) // max hclen (0b1111) + 4

for i := 0; i < (hclen + 4); i++ {

codeBitLengths[codeLengthOffsets[i]] = readBitsInv(stream, 3)

}

return codeBitLengths

}

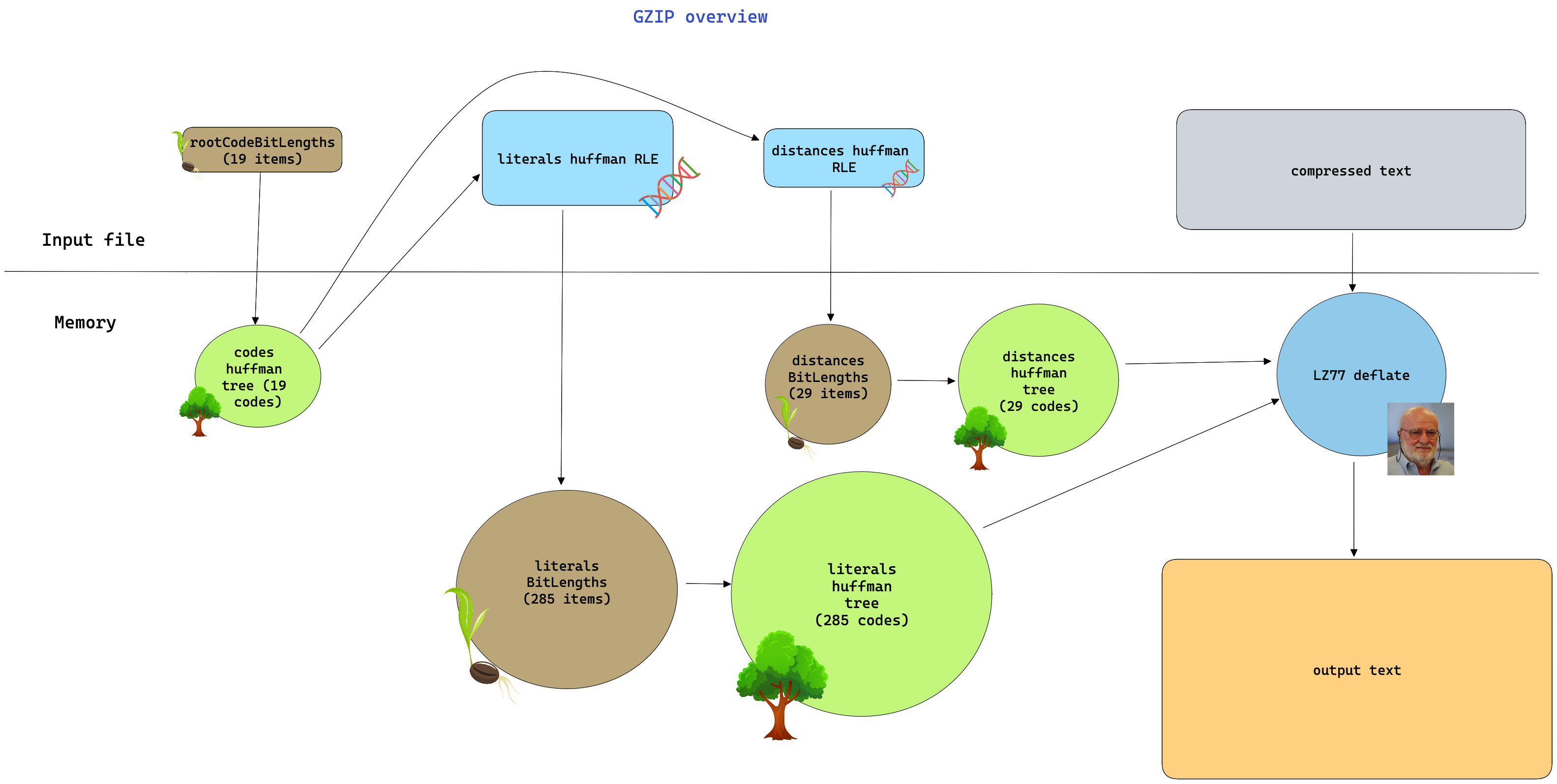

So we will have this up-to 19 symbols (maximally 57 bits) huffman tree, which we will use to build the 285 codes literals huffman tree.

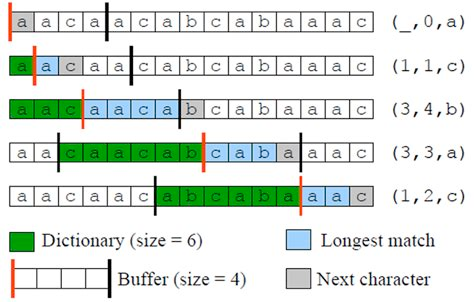

Technique 2: LZ77

LZ77 is a data compression algorithm published by Lempel and Ziv in 1977 (not to be confused with LZ78 (see footnote), which is similar but slightly different). In principle, LZ77 maintains a sliding window where we can reference some earlier data in the sliding window.

One implementation could be to have triplets of data: (back pointer, copy-length, next_byte) as such:

Notice the triplet like (3, 4, b), the string aaca is a self-reference. (the last a in the blue box refers to first a in the blue box). This always happens when copy-length is bigger than back-pointer.

The actual LZ77 implementation used in GZIP slightly more complicated for more efficient use of space. It doesn’t use the triplet, but rather differentiate literals and “back-pointers”.

LZ77 in GZIP

Consider we have this body of text (char count 1408 chars)

So shaken as we are, so wan with care,

Find we a time for frighted peace to pant,

And breathe short-winded accents of new broils

To be commenced in strands afar remote.

No more the thirsty entrance of this soil

Shall daub her lips with her own children's blood;

Nor more shall trenching war channel her fields,

Nor bruise her flowerets with the armed hoofs

Of hostile paces: those opposed eyes,

Which, like the meteors of a troubled heaven,

All of one nature, of one substance bred,

Did lately meet in the intestine shock

And furious close of civil butchery

Shall now, in mutual well-beseeming ranks,

March all one way and be no more opposed

Against acquaintance, kindred and allies:

The edge of war, like an ill-sheathed knife,

No more shall cut his master. Therefore, friends,

As far as to the sepulchre of Christ,

Whose soldier now, under whose blessed cross

We are impressed and engaged to fight,

Forthwith a power of English shall we levy;

Whose arms were moulded in their mothers' womb

To chase these pagans in those holy fields

Over whose acres walk'd those blessed feet

Which fourteen hundred years ago were nail'd

For our advantage on the bitter cross.

But this our purpose now is twelve month old,

And bootless 'tis to tell you we will go:

Therefore we meet not now. Then let me hear

Of you, my gentle cousin Westmoreland,

What yesternight our council did decree

In forwarding this dear expedience.

After applying LZ77:

So shaken as we are, so wan with c<16,4>(are,)

Find<12,5>( we a) time for frighted peace to pant,

A<41,3>(nd )breathe<2,3>( sh)ort-w<40,3>(ind)<64,3>(ed )accents of new<85,3>( br)oils

To be commenc<104,3>(ed )in strands afar remote.

No mor<71,3>(e t)h<175,4>(e th)irsty <110,3>(ent)<150,3>(ran)<70,3>(ce )<115,3>(of )<181,3>(thi)s<20,3>( so)il

Shall daub her lips<27,6>( with )<222,4>(her )own children's blood;<168,3>(

No)r<171,6>( more )s<212,5>(hall )t<249,3>(ren)<244,3>(chi)ng<23,3>( wa)r<243,3>( ch)annel<235,5>( her )fields,<261,5>(

Nor )bruise<298,6>( her f)loweret<229,7>(s with )<177,4>(the )arm<142,3>(ed )hoofs

Of<350,3>( ho)stile<75,3>( pa)ces:<340,3>( th)o<319,3>(se )opp<377,3>(ose)d eye<308,3>(s,

)Which,<225,3>( li)k<175,6>(e the )meteor<113,5>(s of )<47,3>(a t)roubl<348,4>(ed h)eaven<80,3>(,

A)<274,3>(ll )<419,3>(of )one natu<17,4>(re, )<445,7>(of one )subst<193,5>(ance )<86,3>(bre)d,

Did lately<410,3>( me)et<144,4>( in )<407,4>(the )inte<362,3>(sti)n<92,5>(e sho)ck<81,5>(

And )furious cl<377,5>(ose o)f civil butc<322,3>(her)y<210,7>(

Shall )now,<498,4>( in )mutual<43,3>( we)ll-beseem<283,4>(ing )<192,3>(ran)k<392,3>(s,

)March <560,4>(all )<463,4>(one )way a<83,4>(nd b)<450,3>(e n)<170,7>(o more )<381,7>(opposed)

Against<106,3>( ac)qu<644,3>(ain)<471,5>(tance), k<101,3>(ind)r<104,4>(ed a)<620,3>(nd )<607,3>(all)i<371,3>(es:)

T<503,3>(he )edg<538,5>(e of )<287,3>(war)<400,7>(, like )<25,3>(an )i<581,3>(ll-)sh<88,5>(eathe)d knife,<168,9>(

No more )<271,6>(shall )cut <202,4>(his )master. <684,3>(The)re<54,3>(for)<661,3>(e, )<58,3>(fri)en<307,4>(ds,

)As <157,4>(far )<10,3>(as )<73,3>(to )<90,5>(the s)epulchr<691,5>(e of )Christ<393,4>(,

Wh)<536,4>(ose )soldi<323,3>(er )<564,5>(now, )u<102,3>(nde)r w<818,5>(hose )<428,3>(ble)s<385,4>(sed )cross

W<14,5>(e are) impr<850,6>(essed )<672,4>(and )engag<876,3>(ed )<789,3>(to )f<60,4>(ight)<37,3>(,

F)<96,3>(ort)h<336,5>(with )a p<328,4>(ower)<805,4>( of )English<736,7>( shall )<44,3>(we )levy;<816,7>(

Whose )<345,3>(arm)<11,4>(s we)<866,3>(re )mould<142,6>(ed in )<792,3>(the)i<264,4>(r mo)<972,3>(the)rs' womb<128,4>(

To )<291,3>(cha)s<405,5>(e the)s<366,4>(e pa)gans<968,6>( in th)<947,4>(ose )ho<491,3>(ly )<303,6>(fields)

Ov<839,9>(er whose )ac<872,3>(res)<695,3>( wa)lk'd<1016,7>( those )<848,8>(blessed )f<495,3>(eet)<394,6>(

Which)<53,3>( fo)urte<7,3>(en )hu<666,6>(ndred )yea<416,3>(rs )ago<955,6>( were )nail'd<900,4>(

For) <1085,3>(our) adv<77,3>(ant)a<690,4>(ge o)<500,6>(n the )bit<754,3>(ter)<855,6>( cross).

B<744,3>(ut )<201,5>(this )<1127,4>(our )pur<636,4>(pose)<830,4>( now) <1168,3>(is )t<579,3>(wel)v<959,4>(e mo)n<908,3>(th )<824,3>(old)<80,7>(,

And b)oot<1066,4>(less) 'ti<787,6>(s to t)<580,3>(ell) you<935,4>( we )w<709,3>(ill) go<682,5>(:

The)<762,6>(refore)<1237,4>( we )<494,5>(meet )no<1266,4>(t no)w<757,5>(. The)n<938,3>( le)t<1262,3>( me)<432,4>( hea)r<356,4>(

Of )<1234,3>(you), my g<189,3>(ent)l<133,4>(e co)us<1014,3>(in )W<509,3>(est)<732,4>(more)l<879,3>(and)<815,4>(,

Wh)at<1100,3>( ye)<753,4>(ster)n<895,4>(ight)<1170,5>( our )<1312,3>(cou)nc<546,3>(il )d<484,3>(id )de<1047,3>(cre)e

In<53,4>( for)<696,3>(war)d<590,4>(ing )<1166,5>(this )d<1290,3>(ear) expe<826,3>(die)<659,3>(nce).

Summary Report: literalCount 599, backPointerCount 202, totalBytes 1408

We can get reduce the space usage until only 42.5% of the original space (ignoring all the overhead first for now). The actual space usage maybe around 50-60% of original.

But how do we actually encode back pointer? One naive solution is to use escape characters to differentiate the metadata (back-pointer) from the literals. However this might not have good performance. In GZIP, actually we don’t even store the literals as literal, however, as huffman code!

Here’s a simplified snippet from the implementation:

for {

node := resolveHuffmanCode(literalsRoot, stream)

if node.code >= 0 && node.code < 256 {

// literal

buf = append(buf, byte(node.code))

} else if node.code == 256 {

// stop code

break

} else if node.code > 256 && node.code <= 285 {

// This is a back-pointer

// get length

var length int

if node.code < 265 {

length = node.code - 254

} else {

length = getExtraLength(length, stream)

}

// get distance (from huffman tree)

distNode := resolveHuffmanCode(distancesRoot, stream)

dist := dist.code

if dist > 3 {

dist = getExtraDist(dist, stream)

}

// read backpointer

backPointer := len(buf) - dist - 1

for length > 0 {

buf = append(buf, buf[backPointer])

length--

backPointer++

}

} else {

panic("invalid code!")

}

}

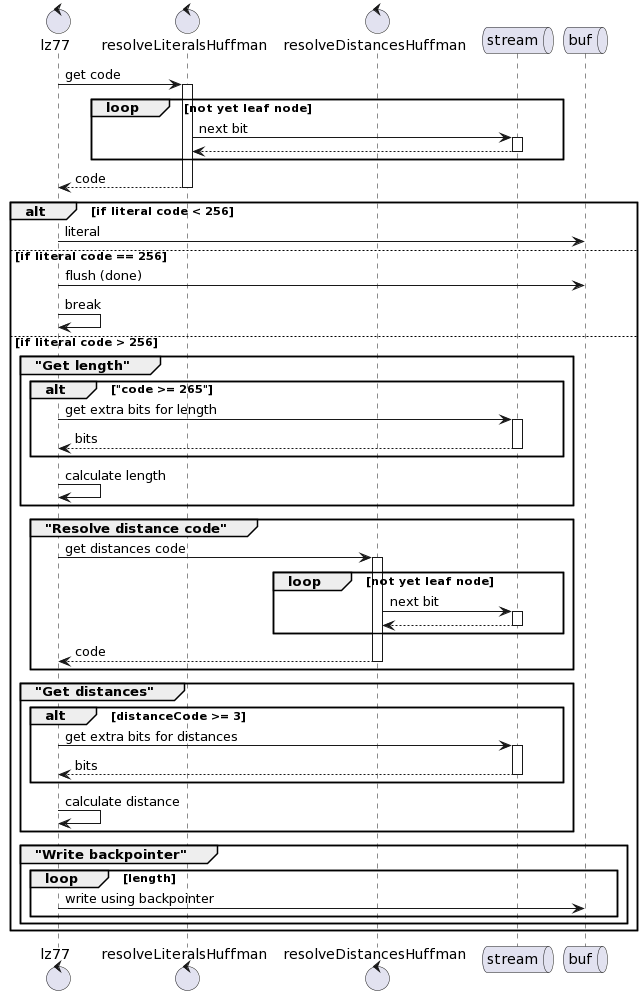

If you notice here there are two huffman trees being used: literalsTree and distancesTree. We will discuss about the construction of the tree later. Here is flow of data:

control lz77 as outer

control resolveLiteralsHuffman

control resolveDistancesHuffman

queue stream

queue buf

outer -> resolveLiteralsHuffman++: get code

loop not yet leaf node

resolveLiteralsHuffman -> stream++: next bit

resolveLiteralsHuffman <-- stream--

end

outer <-- resolveLiteralsHuffman--: code

alt if literal code < 256

outer -> buf: literal

else if literal code == 256

outer -> buf: flush (done)

outer -> outer: break

else if literal code > 256

group "Get length"

alt "code >= 265"

outer -> stream++: get extra bits for length

outer <-- stream--: bits

end

outer -> outer: calculate length

end

group "Resolve distance code"

outer -> resolveDistancesHuffman++: get distances code

loop not yet leaf node

resolveDistancesHuffman -> stream++: next bit

resolveDistancesHuffman <-- stream--

end

outer <-- resolveDistancesHuffman--: code

end

group "Get distances"

alt distanceCode >= 3

outer -> stream++: get extra bits for distances

outer <-- stream--: bits

end

outer -> outer: calculate distance

end

group "Write backpointer"

loop length

outer -> buf: write using backpointer

end

end

end

The tecnhique used in getting the extra distances and extra lengths is similar to the earlier code 17, 18. That is, having variable count of extra bits + the base offset.

Putting it all together

Demo

Live demo or backup video:

Actual performance:

- Shakespare: uncompressed 1408B, compressed is 822B. Means it’s 58% ratio

- Feynman lecture: uncompressed is 37106B, compressed is 13337B, Means it’s 36% ratio.

Generally the bigger the file should have better compression because more back-referencing.

Footnote

LZ77 and LZ78 difference is only slightly but fundamental. LZ77 builds the “shortcut dictionary” on the fly, referencing earlier data. LZ78 will pre-calculate the “shortcut dictionary”, which then can be used as building blocks. There is no concept of “back-pointer” in LZ78, only “pointer” where one dictionary entry can refer to more simpler dictionary entry. A bit like defining “going” by referencing “go”.

The main drawback of LZ77 compared to LZ78 is the need to keep the sliding window. LZ78 can build dictionary items from anywhere within the compressed text. However, the drawback of LZ77 also means it can be used for streaming applications like media streaming in the web, meanwhile LZ78 couldn’t.